Arrival

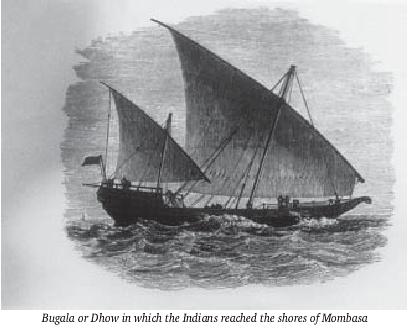

Indians have been voyaging to East Africa since 1000 BC, long before the African continent was awoken by the white man. There is much documentary evidence to this effect in the Indian literature by mentioning their voyages in dhows and small boats. The earliest sailors recorded are Kanji Maalam and Raamsinh Maalam (they are referred to as "nakhuda" (meaning master of the dhow)).

They carried rice, millet and wheat with them bargaining for gold, ivory and wax. It was during one such voyage that Kanji Maalam (also referred to as Kana Maalam) came face to face with Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese explorer who was lost at sea and rescued him and escorted his ship to the port of Calicut, India on 22nd May 1498. The Portuguese have recorded the meeting between them as:

"These Indians are tawny men; they wore but little clothing and have long beards and long hair, which they braid. They told us they ate no beef. Their language differs from that of the Arabs, but some of them know a little of it, as they hold much intercourse with them"

Freeman-Granville The East African Coast (Vasco da Gama's Discovery of East Africa for Portugal 1498. p.55, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1962).

"Indians have traded up and down the East African Coast for centuries"

Patrick Balfour: Lords of the Equator.

Travel Book Club, London 1938

The Indian's knowledge of East Africa goes back thousands of years, as the Mountains of the Moon and the source of the Nile are mentioned in the Ancient Hindu religious literature called "Puranas". Many Indian researchers and the historians believe that East Africa and India was once a single continent until the land between the two disappeared under the sea, parting the continents.

These are an authoritative record of India's relationship with East Africa. Vasco da Gama was stunned with the beauty of India, so much so, that he decided to establish a base in India that resulted in Goa being seized and occupied by Alfonso de Albuquerque of Portugal in 1510. For the next two centuries Portuguese was the dominant power in the Indian Ocean. The sea voyages became unsafe due to Portuguese and later Arab piracy.

The Portuguese interest in voyaging to the coast was mainly to plunder the gold and ivory when they descended usually at six months intervals when the sea was calm and the journey comfortable.

With the occupation of Goa in India, the Portuguese desire for colonialism increased and as a result, Mombasa was occupied. The Arabs resisted but they had no answer to Portuguese superior weaponry. The Portuguese colonial rule began.

They built a formidable fort naming it Fort Jesus from where they could observe the sea for any danger from dhows or ships, as Zanzibar, which was under Arab rule, was only 125 miles away.

The Arab resistance continued. They had the advantage of manpower and the population's support. The siege of Fort Jesus began in 1696 and the war lasted for nearly two years and the Arabs were successful in scaling the fortress. The enemy garrison escaped in ships anchored at the harbour.

Mombasa was again under Arab rule but there were internal rivalries amongst them and it was an obstacle for any commercial development. No Indians or Europeans are recorded to have been in Mombasa during this period. The Portuguese and Arab ocean piracy continued.

Again, it was an Indian who raised his head and sword against this unholy and unsocial dominance. His name was Ranmal Lakha, one of the bravest Lohana warrior, who was born in a very poor family. As a young boy, he arrived in Bombay selling fans at two paisa and made a living and later got employed at five rupees per month on a dhow, subsequently raising higher to fifteen rupees and taking over the sole charge of the dhow.

It was on one such journey near Bombay that he rescued Governor Hornby's ship from sinking and later became the Governor's right hand man and with his help became the owner of the dhow and later fleets of ships.

By now, British administration was rooted in India but somehow, the ocean piracy continued without hindrance. Either the British didn't care or couldn't tackle the problem. It was one incident that brought an end to sea piracy.

About ninety Indian women were either abducted or paid for and shipped on an Arab dhow for the Arabian Sheiks' harems. Ranman Lakha was informed of this incident and immediately prepared his vessel with his few brave colleagues and pursued the Arab dhow, stormed it, killed the pirates and rescued all the women, who were all so much overcome with emotion that they took off Kumkum (red turmeric) from their foreheads to put a tilak (mark of pigment) on Ranmal Lakha's forehead.

He vowed there and then to make the pirate and bandit ridden Indian ocean safe and had the full support of the British Governor with gunboats to wipe off the buccaneers who roamed the seas. The other two, Haji Kassam Suleman and Padamsinh Shah are recorded to have joined in the effort. The Indian Ocean was made safe for travel.

In the initial stage the Indians began to trade in Muskat, Oman, that was ruled by an Arab Imam who occupied Zanzibar and invited Indians and Arab traders from Oman to trade and settle in Zanzibar. Thus began the Indian settlers' tale of East Africa. One name recorded just as Jeevanjee was in Zanzibar in 1818.

The Indian migration to Africa in large numbers began in 1739, when Nadir Shah invaded India ending the Moghul rule. The invasion was an open invitation to anarchy.

The tiny kingdoms who were under Moghul rule declared themselves independent and the castes Zala, Gohil, Bhil, Kathi, Maher and others fought amongst themselves to settle old scores.

It was during this period that Indian began to settle in Oman and subsequently Zanzibar. Again, it was during this time that Indian seafarers invented the name Jungbar, Jung meaning a sea faring trading boat and bar meaning a port, a place to anchor.

The British have a habit of changing every name according to their liking. No wonder Jungbar was converted to Zanzibar.

Many Indians were in Oman. Known names in Oman were Damodar Dharamshi, Ratanshi Purshottam Raja, Daulatgiri Gosai and Virjee Bhatia. Unfortunately, nothing is known about their descendants so far. Neither are written documents in existence.

Gokaldas Khimji who immigrated to Oman in early 1800 used to trade by riding on a donkey. He was known as "Mamubhai" amongst the local Arabs. Sultan of Oman was stubborn, that no one should be allowed to own a motorcar except himself. He only made an exception for Gokaldas to own one.

The Sultan left Oman to his brothers and moved to Zanzibar making it his capital. Sultan Sayyid Sayed, apart from being a ruler, was a shrewd businessman and it was he who introduced clove plants and owned many farms which he entrusted to Indians to look after and later sold a few to them. It was the Indians who developed the export business making cloves the chief cash crop.

The Sultan was appreciative of their hard work and honesty and encouraged and invited more to settle in his country through rulers and princes of tiny Indian kingdoms, one of them was Roa of Cutch, who was his close friend.

The Arabs ended Portuguese rule in the Kenyan port of Mombasa and the Indians were encouraged to settle there.

In Zanzibar, sultan's prime minister (called diwan) was an Indian of Bhatia caste from the village if Mundra. His name was Jairam Shivji who was assisted by his brother Abji Shivji.

The two administered the country excellently and looked after all the customs affairs as chief officers as well as owning their own trading firms.

There is written evidence that India's trade routes stem back to the first century AD. Vasco da Gama arrived on the east coast of Africa in 1498 whilst searching for India. He captured Mombasa and from this time until 1728 there was intermittent war between the Portuguese and the Arabs. Eventually the Sultan of Oman, Salim Bin Ali, defeated the Portuguese. The Arabs were mainly traders travelling between the East African Coast and Oman in dhows and with the assistance of the seasonal monsoon winds.

The Sultan developed a friendship with the British and Mombasa came under British rule in 1880 through the East Africa Company.

The Indians were not motivated by political self- interest or territorial ambition unlike their British, German and Portuguese counterparts, who combined trading activities with colonial expansion. During the reign of the Sultan, Said-bin-Said, many Indians used to leave their homes and families and embark on lonely journeys to East Africa, by dhow, which would last for a year to eighteen months. The wise Sultan, eager to speed up and encourage business transactions, invited them to bring their families to join them. He promised to honour and protect traditional values and religious beliefs. He appointed Indians to posts of administrative responsibility.

Merchant seamen from India's western coast have traded with Arabia and the east coast of Africa since earliest times. Traders from Kutch, Porbander and Surat (all in modern day Gujarat) have a long history of providing commercial and banking services to the populations in the Persian Gulf. (Pryor, K., 12/04/94)

In the early 19th Century the Sultan of Muscat shifted his capital to Zanzibar, an island off the coast of Tanzania, and he invited Indians who traded around Muscat to set up business in the new capital. He appointed a wealthy Indian businessman, Wat Bhima, to be Collector of Customs, one of the most important political and commercial offices in Zanzibar. The Sultan also promised both Hindus and Muslims that they could practice their own religious customs without persecution. This liberal policy encouraged more Indians to set up business in Zanzibar and soon they were the most important trading community in the region. Many European and American trading companies used Indian credit and Indian agents to buy and sell their goods locally. Indian firms provided loans to the Sultan and also to the Swahili and Arab merchants who controlled the trade of inland East Africa (Pryor, K., mimeo 12/04/94).

By 1860, about 5-6,000 Indians were living in Zanzibar. Many were from Kutch and Porbandar; others came from around Bombay and Goa and the port of Karachi (now in Pakistan). Amongst the Hindus there were Bhattias, Lohanas and Vanias (Banias). There were also many Muslim traders from the Khoja, Bohra and Memon communities of Gujarat and Sindh. The Muslims usually brought their families with them and settled permanently in Zanzibar, but most of the Hindu traders came to Zanzibar along and planned eventually to return to their wives and children in India. (Pryor, K., mimeo 12/04/94)

In the 19th Century most of the trade was in cloth, metal and glass. The Indians would sell cottons and glass beads to the Swahilis and Arabs who traded in the interior of East Africa and in return would buy from them African ivory, copper and cloves for sale in India and Europe. (Pryor, K., mimeo 12/04/94)

In the 1880s when the European Imperial powers began carving up Africa into colonies, it was the Indians with Zanzibari experience who moved into British East Africa. The Imperial British East Africa Company relied heavily on British Indian administrators and from 1888 onwards Indian soldiers were used in expeditions and military operations in East Africa (Pryor, K., mimeo 12/04/94).

Many Asians were also recruited by the British to build the East African railways system to connect East African trade with the rest of the world. At the opening of the Kenya highlands for settlement, Asians had sought equal share with the British. When the British whites pressed their demand upon the Colonial Office in London for representative government in Kenya, as a step to the establishment of a white dominion, Asians demanded equal representation. As the colonial system flourished, Asian businesses began to expand.